Selma Blair's life is not a montage and neither is mine

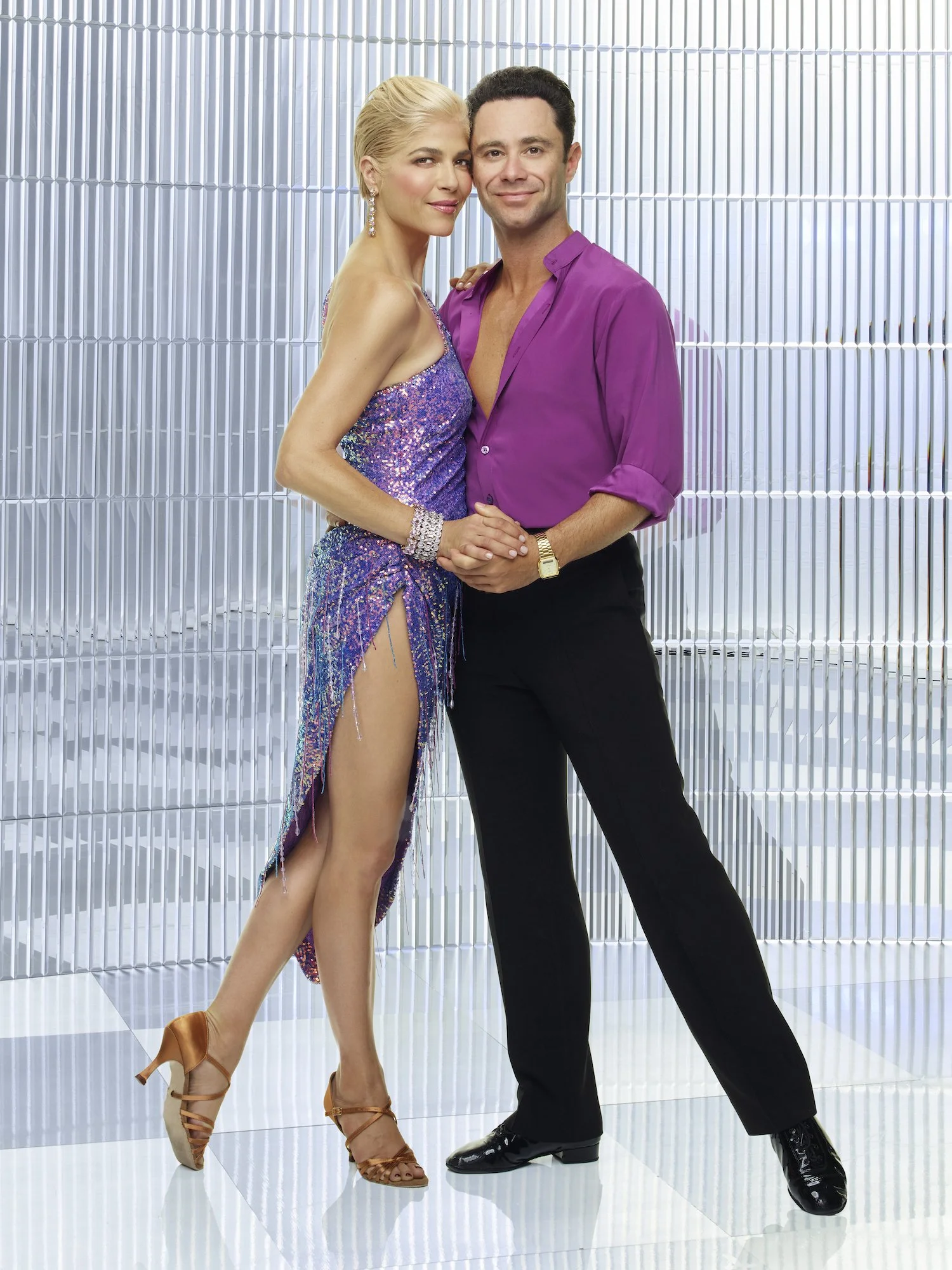

Monday night, actress Selma Blair self-eliminated from Dancing With The Stars.

The show has been on for 31 seasons, and I’ve admittedly watched nearly all of them. As a kid who grew up loving Dirty Dancing (and its deeply underrated sequel, Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights), I was a sucker for a show where non-dancers suddenly became incredible performers via blood, sweat, and power montage. I love the choreography, I love the kitschy video packages, I love the theme nights, and I love the pros.

So when DWTS announced there would be not one but TWO disabled cast members this season, you could say I was pretty fucking hyped to tune in. Even better, one of the two would be one of my favorite 90s actresses, Selma Blair, who I watched in Cruel Intentions so often from 2004-2007 that my sister and I could recite the monologues—and whose incredible memoir, Mean Baby, I’d just finished reading.

All of this is to say that I knew Selma Blair’s run on Dancing With The Stars would be important to me. A person I deeply admired and identified with through chronic illness was going on a show I have loved for 15 years. The dances would be beautiful and her story would serve as incredible representation for people living with Blair’s condition, multiple sclerosis, and other incurable diseases like it. Knowing all of that going in still didn’t prepare me for exactly how much Blair’s run on the show—and her exit—would mean to me.

Selma Blair was not voted off of Dancing With The Stars—in fact, she was scoring well and probably could have continued on for weeks, from a scoring and audience votes perspective. Instead, she made the choice to step away from the show because, in spite of how badly she wanted to dance, the rehearsals and performances were taking too much of a toll on her body.

“This is a dance for everyone that has tried, and hoped that they could do more, but also the power in realizing when it’s time to walk away.”

- Selma Blair, October 17, 2022

As a culture, we love stories of disabled people overcoming all the odds and succeeding anyway. While I’m not saying that never happens, when those narratives are all the public sees in media and news, it creates an extremely reductive and often inaccurate trope of the disabled experience. “Inspiration porn” is everywhere: stories of people overcoming seemingly insurmountable physical odds to walk again, to run the marathon, to push through the pain and prove themselves equal to their able-bodied peers in all the arenas those peers are measuring as important.

Inspiration porn isn’t just annoying—it’s actively harmful to the pursuit of disability justice. It applies the same “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” ethos to disabled people that has been failing workers for decades by suggesting that if disabled people tried harder, they too could overcome in the same way as this one shining example—ignoring factors like socioeconomic status, severity of their symptoms, and other pieces of the puzzle that make us humans with access needs. That narrative also allows non-disabled people to look away from complex stories of disability that might challenge our long-held beliefs in favor of bright and shiny stories of inspiration that can be told without nuance in a 4-minute package on The Today Show.

But Blair didn’t rise up and beat MS with the power of dance and positive thinking. Blair’s story is important because it is, all too often, the real, much messier story of disability: trying, sometimes succeeding, sometimes failing, sometimes having to know when to stop, having to know when you can’t. I can’t do anything an able-bodied person can do. That’s real life. That’s okay.

The moments in my life when I have had to pull back or give up an opportunity because I was too sick have been some of the most difficult moments of my life. But we can’t make the difficult parts of life go away by pretending they don’t exist. My sick peers and I have missed jobs, dates, dances, degrees, and everything in between. What is worse than having to give something up is being told you cannot grieve about that loss publicly because it is not the narrative about disability that is packageable for public consumption. It’s not the story people want to hear.

So thank you, Selma Blair, for showing me a disability narrative that I can see myself in. And in doing it on a platform like Dancing With The Stars, which reaches the homes of so many people who may not be well-versed in disability justice yet: Thank you for showing those people that there is immense strength in knowing when it is time to rest.